https://orthosphere.wordpress.com/2020/05/26/nietzsche-the-diabolical-saint-of-acceptance/

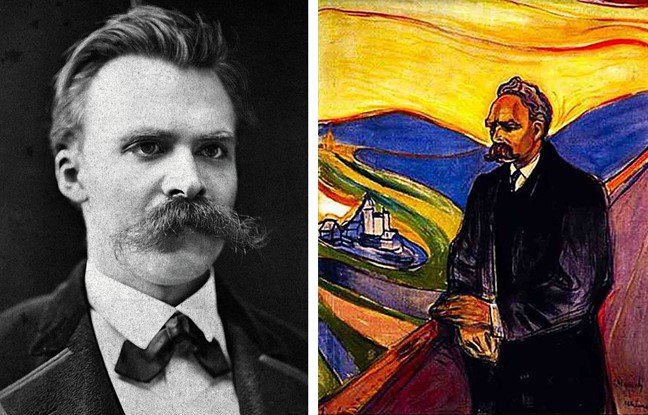

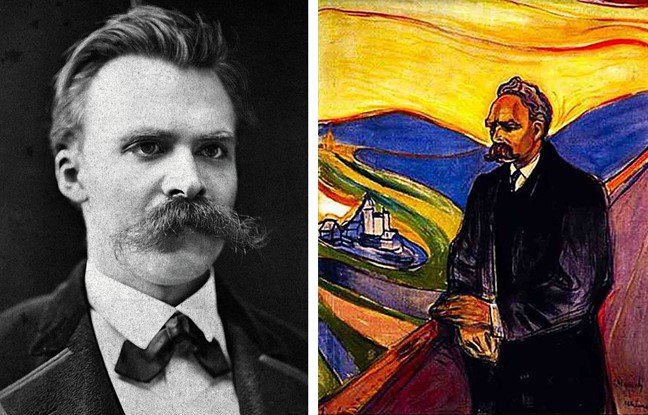

Friedrich Nietzsche is a strange mixture of conflicting impulses; so

chronically sick that writing was a physical agony for his eyes and his

stomach permanently bothered him, yet he wrote paeans to the strong and

mighty. A brilliant analyst of resentment, he had every reason to feel

ignored being unread during his lifetime and self-publishing books that

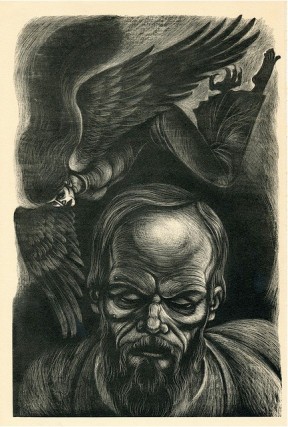

he mostly could not sell. He admired Dostoevsky, which itself is

admirable, writing in

Twilight of the Idols that Dostoevsky was the only psychologist from whom he had anything to learn. Nietzsche first stumbled upon Dostoevsky’s

Notes from Underground in a bookstore in Nice in the winter of 1886-87 and immediately loved it, though Dostoevsky never knew of Nietzsche.

Notes from Underground is

psychologically and anthropologically penetrating, exploring themes of

mimesis and resentment that were of immense interest to Nietzsche.

Unlike Dostoevsky, there is something perennially adolescent about

Nietzsche, perhaps because young adults are often trying to decide what

values they should hold, often temporarily in contradiction to their

parents, as they prepare to make their way in the world on their own.

Nietzsche’s “transvaluation of values” fits this model nicely. There

used to be a certain kind of young man magnetically drawn to Nietzsche’s

mixture of cleverness, perversity, sense that he had a secret

understanding of things, and man alone and against the world demeanor,

and perhaps there still is.

God is ultimately the source of all value. It is because we are made in the image of God

and

are thus connected with eternity, God, and Freedom that the Person has

supreme intrinsic value. There simply is no way around this fact.

Nietzsche, on the other hand, is famous for the notion that God is dead.

This is usually understood to mean that God is dead as a cultural

phenomenon; that all the smart people have become atheists. René Girard

argues in

Dionysus Versus the Crucified, however, that this is a

misunderstanding and that the truth is far more complicated. Nietzsche

rejected Christianity in favor of a return to pagan religion and

Dionysus. Dionysus is a trickster god who stirs up trouble, encourages

his own murder by challenging the social hierarchy, only to magically

reappear unharmed afterwards. This is because Dionysus represents the

scapegoat who is falsely blamed for generating a complete social

breakdown in a way that only a god could achieve, who is then murdered,

bringing the community together in shared hatred, unanimity minus one,

and is then credited with creating widespread peace, again in a god-like

manner.

The Bacchae

The Bacchae

by Euripides, “Bacchus” being another name for Dionysus, depicts the

threatening, implacable, and undefeatable nature of the scapegoating

dynamic. Dionysus, a long-haired beautiful and effeminate youth, has a

reputation for stirring up the Bacchae, the female followers of Bacchus,

into a mad murderous frenzy that would likely include wild drinking.

Pentheus, the king of Thebes, wants nothing to do with Dionysus and

tries to eject him from the city but, failing that, ends up imprisoning

him. Dionysus warns Pentheus that he will be sorry for interfering with a

god, an earthquake sets Dionysus free from his prison, and everything

goes to hell for Pentheus who loses his head, literally, at the hands of

his own mother who has become one of the bacchants.

Nietzsche rejects the Christian God of compassion, and opts for the

pre-Christian Dionysus who is killed and then revives. God is dead, long

live God. Dionysus dies that we may be saved over and over again. The

strong murder the weak; and the mob are always stronger than the

individual, as Socrates points out in

The Gorgias, much to the

disgust of Callicles. Nietzsche sides with Callicles in praising the

strong, but his position suffers from the same defect. The many, the

rabble, can beat the few. Nietzsche then finds himself in the ludicrous

situation of defending the strong against the weak, a logically and

rhetorically contradictory position. In Christianity, as Nietzsche sees

it, the slaves have risen up against their masters and denounced

brutality, praising forgiveness and compassion, tricking the strong, the

masters, into feeling guilty for callously mistreating their social

inferiors. Nietzsche is correct that the weak are prone to

resentment,

that unlovely emotion and attitude, but it is better than the strong’s

treatment of the weak. Repressed violence is better than violence

expressed.

Unlike many nineteenth century anthropologists and critics who

equated the savior aspect of Dionysus and other sacrificial religions

with Jesus’ death, Nietzsche recognized that Dionysus is the antithesis

of the Crucified. The immolation of Jesus reveals the scapegoat

mechanism because he is recognized as an innocent victim murdered at the

hands of the mob. Up until then, this habit of murdering the scapegoat

went unnoticed partly because the victim was not alive to complain about

his unjust treatment. With Jesus, the disciples were steadfast in

maintaining Christ’s innocence with supernatural courage, since

defending the scapegoat puts someone at odds with the mob who are likely

to treat him with the same rough justice they meted out to the victim.

So, Nietzsche had enough insight to recognize what made Jesus different.

Thus Spake Zarathustra

Thus Spake Zarathustra

is where Nietzsche announces the death of God and has the prophet claim

that we have murdered him with our bloody knives. Girard points out

that this is simply not taken seriously by many critics who imagine that

he is referring to the Christian God and that the reference to knives

is strictly metaphorical. But it is Dionysus the god, the scapegoat

victim, that we kill with our knives whereupon he is resurrected as

immortal savior, to begin the process all over again.

Nietzsche wants a transvaluation of all values, but since the

Christian God is the source of all values and Nietzsche is an atheist,

he is unable to generate value at all. What he calls “master” morality

in

The Genealogy of Morals is the absence of morality. It is in

line with Callicles’ description of the strong who simply take what

they want. Here Callicles uses the demi-god Heracles (Hercules in Latin)

as his example, swooping in to take another man’s cattle. The fact that

Heracles is half-god is relevant. Heracles, the man who murdered his

whole family and thus is the arch-villain scapegoat victim, also plays

savior as the most heroic of all Greek heroes. One thing Nietzsche

claims to like about the “masters” is that they do not hate or resent

anyone. They have no envy and anyone below them socially is unworthy of

their attention. They have eyes only for their social equals with whom

they might compete, but who they also respect. The weak are simply

beneath contempt.

Nietzsche is concerned that Christianity and the morality of his time

were a kind of cult of equality and thus mediocrity. Rather than

admiring the cultural high achievers, like himself perhaps, Nietzsche

worried that it was the meek, the humble, and most of all, the

innocuous, who were esteemed. Many of Nietzsche’s criticisms of

Christianity are really attacks on the Christianity of his time which

had many unappealing features. He certainly was not a fan of boring

bourgeois sentimentality or the idea of eternal damnation. The

difficulty is that there is no way to get value from a Godless,

naturalistic, view of reality. So Nietzsche is reduced to impotency. He

wants an alternative to values derived from theism, but is noticeably

and initially perplexingly unenthusiastic about “master” morality. His

heart was not in it. Mastery morality seems to play the role of a

place-filler until he can come up with something better, but of course,

he never does and he just flails around.

Nietzsche rejects the boring, mediocre, and banal aspects of the

morality and religion of his time, but then he accepts the equally

boring and banal aspects of scientifically inspired metaphysics,

naturalism, also popular in his era. This is a total failure of

imagination. But it also represents a genuine dichotomy. Once a belief

in the Kingdom of God, of heaven, the transcendent, and the divine is

abandoned, what is left is mere physical reality, and physical reality

as a sequence of events is deterministic and thus meaningless and

unlovable. It is only when some of those events point back to their

origins in the spiritual realm of subjectivity, and thus agents, that

determinism can be escaped.

What Nietzsche needed to do was to criticize socially-derived

malformations of Christianity and replace them with a more genuine

Christian vision. This can be difficult because science and religion as

social phenomena have the great mass,

Das Man, backing them up.

This creates orthodoxy and makes of the free thinker a heretic.

Nietzsche’s acquiescence to many scientific tropes is surprising given

his iconoclastic attitude to religion. Clearly religion and myth

inspired his imagination more than science did. Dostoevsky’s character

Ivan in

The Brothers Karamazov at least criticizes a very

sophisticated version of Christianity and attacks it well, despite

Dostoevsky’s pro-Christian sentiments.

To understand what is going wrong with Nietzsche’s thought it is

necessary to understand Ken Wilber’s argument that the proper

existential stance requires both wisdom and compassion, Eros and Agape,

symbolized by the allegory of Plato’s Cave. In leaving the cave, the

philosopher, the lover of wisdom, is searching for wisdom, salvation,

God, the Good, and happiness. For Plato, happiness requires wisdom

because it is necessary to learn the difference between what is truly

desirable and what is not. Part of man’s destiny is to develop. Misery

and suffering will lead to wanting to overcome the problems and

limitations that cause these things. The quest to understand the Good

better is everyone’s life long goal, whether they know it or not.

So, to care about yourself and for other people, it is necessary to

strive to develop and to wish them to do so as well. To wish anyone to

stop developing at any age is to wish him ill. The interests and

limitations of a ten year old are fine when he is ten, but ridiculous

when he is fifteen. But a proper existential stance also requires

compassion. Compassion is acceptance; unconditional love symbolized by

returning to the cave out of concern for the philosopher’s fellow

prisoners.

Wilber calls the quest for development and improvement “Eros,”

related to the love man has for God, and equates it with a more

masculine-style conditional love, and unconditional compassionate love

he calls “Agape,” the love God has for man, which he regards as being

more nurturing and feminine in nature. He argues that both Eros and

Agape are necessary for either one to exist properly and thus that each

individual should embody both of these tendencies. Traditionally, the

proper raising of a child entails a father demonstrating an Eros form of

love, pushing the child to develop and setting standards, and a mother

who loved her child unconditionally no matter what wrongs he might

commit, loving all her children equally. Men and women can play both

roles as needed, though boys without actual fathers are statistically

more likely to end up being violent, drug or alcohol addicted, and to

have worse vocational and educational achievements.

The quest for development can be taken too far. Puritanism and

Gnosticism strive for salvation only and regard the body and physical

reality as evil; as a nasty hindrance barring our way to happiness.

Sparta represents an example of a culture that over-emphasized Eros. The

Spartans, driven by fear of an uprising by the Helots, the usually

Greek slaves they kept that far out-numbered them, embraced a very

brutal, friendless, social existence designed to generate the ultimate

warriors. They represent a very Eros-only form of life. A Spartan mother

is supposed to tell her son to come back either with his shield or on

it.

The urge for compassion and acceptance can be overdone as well.

Fertility Cults unconditionally accept nature just as it is. Culture can

come to be seen as life-denying. To strive to develop is regarded as

rejecting reality as you find it. However, since failing to develop is

failing to live well, this excessive compassion in isolation is bad.

Idiot compassion, as Wilber calls it, involves accepting everything with

no urge to develop. A parent gives his kids candy and TV because “it’s

what makes them happy.” One spouse allows the other to beat him up

because he loves her. Medals are given for just showing up, Valentine’s

Day cards are given by school children to every single classmate,

rendering the cards meaningless, and children are told “good job” when

the activity was not done well at all. Compassion without wisdom is not

compassionate and caring at all. Instead it hurts people.

The traditional two parent family had the tough love Dad making the

child do his homework and piano practice, sending him to bed with no

supper, and the unconditionally loving mother sneaking him something to

eat late at night. Genuine love involves complete acceptance of your

children no matter what. Even if they become ax murderers, the parent

will visit them in prison. It also involves pushing them to develop

themselves and to develop their talents rather than becoming useless to

themselves and to other people.

Nietzsche goes wrong in his philosophy by being half right. A major

problem and source of error involves mistaking a partial truth for the

whole truth.

[1] It

is often difficult to extricate ourselves from this error because the

thing that is being emphasized is true. The person knows he has hold of a

truth and will not relinquish it. This is part of Nietzsche’s problem.

He knows that compassion and acceptance are good and he is willing to

promote them to the utter demise of compassion and acceptance! But he is

also driven to this partiality through his metaphysical commitments.

Nietzsche says there is no heaven, no transcendence. There is nothing

higher to aim for. What is real is here on Earth and what we see is

nature. Thus, there is no way to exit Plato’s Cave and nowhere to shoot

for. This forestalls the possibility of Eros.

At times, Nietzsche longs to escape the human condition, existing in

the metaxy; between God and animals. He fantasizes about the Übermensch,

the beyond-man, the over man, the superman, breaking free from the

herd, the mediocre, who would create his own values. However, if God is

the source of value, then the Übermensch is impossible. Man creates

value only through the conditions God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (

Ungrund)

provide. For one thing, without the transcendent, determinism reigns,

and thus there is no creativity of any kind, no agents as centers of

feeling, thinking, willing decision-making, because Freedom would not

exist. Man as the image of God is partly free and creative and embodies

supreme value in himself. That value is not created by him, but once so

endowed, he can provide his own meaning to his endeavors.

Eternal Recurrence

Nietzsche, unlike the weak and slave-like people he despises, wants

to say yes to life. His test for whether someone is saying yes to life

is whether he would assent to an imaginary scenario. Do you assent, in

principle, to living the same life you have just lived over and over

again for all eternity without changing anything at all. If the answer

is “yes,” then you are a saint of acceptance. Total acceptance means

saying yes to life in all its aspects and mistakes.

It

should be pointed out that Nietzsche definitely did not believe in

actual reincarnation. This idea of eternal recurrence is just a thought

experiment to determine a person’s fundamental attitude to life. The

question is how someone reacts to the mere thought of this situation.

This is where the partial truth enters. It can sometimes seem nice to

fantasize about editing our lives; taking out all the boring bits, and

the suffering and the times we acted badly. But saying yes to life is

accepting it just as it is. However, what the test of eternal recurrence

misses is embracing development; the striving part. Living the same

life over and over would be a kind of hell because a person would never

get to develop. A good life combines development and acceptance. In

abandoning development, it is Nietzsche who is rejecting an important

aspect of life.

Suffering is fine, as far as it goes. Suffering is a motive to

change, to grow and develop. New parents must develop new capacities for

patience or end up abandoning or murdering their new baby. However, the

kind of suffering Nietzsche is recommending – never learning from your

mistakes and thus never developing, is hell. Developing does not mean

the end of suffering. Old problems are solved and new developmentally

appropriate ones replace them. There are the problems of youth, of

mid-life, and of old age; getting an education and useful skills at one

point, managing a household at another, and finding a way of having a

fulfilling retirement at yet another.

Acceptance is a virtue. We should accept two year olds, for all their limitations. They

cannot

read, or write; they may not even be toilet trained, but they may

still be a perfect little two year old. We are all at some level of

development and are perfect in this way too. But loving that two year

old also means not condemning them to the same mistakes, the same

interests, the same level of cognitive development for all eternity. In

some sense, we are all that two year old. By trying to say yes to life,

Nietzsche says no to life.

What does Nietzsche see in nature? No morality. The strong eat the

weak. It is brutal, but it is the way it is. For Nietzsche, morality

says no to life. Morality tries to uplift the weak, it says that lending

a helping hand is the moral thing to do.. Nietzsche argues that

morality says no to life, to nature. Any attempt to change these basic

facts of life is to say no. We must say yes, and saying yes means

accepting everything. Nature is on the side of the strong, so we should

be too.

Those driven by excessive compassion, Agape, are sometimes attracted

to Nietzsche’s nonjudgmental acceptance. Fans of Eros can admire

Nietzsche’s emphasis on strength, independence, and the self-reliance in

this image of things, where a person is not looking for handouts or

support from others.

In reality, Nietzsche’s view even of nature is inaccurate. “Nature”

features animals working together for mutual survival, both prey and

predator. Mother lions, birds, pandas, wildebeest, etc. care for and

nurture their young. It is not all unrelieved brutality.

There is a certain type of smart, young person who thinks that

accepting total nihilism is manly and admirable. Any deviation from

unrelieved awfulness is mere escapism and fantasy. Ivan Pavlov wrote:

“There are weak people over whom religion has power. The strong ones –

yes, the strong ones – can become thorough rationalists, relying only

upon knowledge, but the weak ones are unable to do this.”

[2]

Since rationalism can only analyze, but not create value, beauty, and

love, only the weak, in this view, will avoid nihilism. In addition,

Pavlov falsely assumes that empiricism produces knowledge but that

philosophical and religious speculation do not. Near unanimous agreement

about the trivial is often possible, while important truths remain

debatable, and this provides the opportunity for human creativity,

imagination, intuition, and freedom.

Evidence of Nietzsche’s acknowledgement of the horror of what he is

arguing and his willingness to accept this horror can be seen in his

comments about Indian “untouchables;” the lowest members of the Indian

caste system. They can wear only used clothing. They may not wash in

fresh water because they would pollute it. They may drink only from the

water that fills where the muddy hoof print of an animal like an ox has

fallen. Nietzsche pretends to delight in this, after going into graphic

disgusting detail. Cultural relativism, that instance of idiot

compassion, would acquiesce to this. “This is the Indian way, we must

not judge.” Unconditional acceptance. And paradoxically, this attitude

might be attractive to lovers of excessive Eros, seeing the untouchables

as the weak who get what they deserve.

Nature, Nietzsche thinks, says yes to “master” morality while

Christian charity is keeping mankind down. Nietzsche claims that Kant

celebrates mediocrity and bourgeois virtues like punctuality as though

that they are the peak of human achievement. If mankind is to achieve

anything, Nietzsche thinks, it must leave the heaving masses behind and

the true genius must rise above the petty self-protective whining of hoi

polloi. The Übermensch will prevail.

Callicles, that Platonic character who inspired Nietzsche, might be

right that generally the many, the weak, are fans of “justice” as

law-abidingness because laws against stealing, violence, and murder

protect the vulnerable more than those able to defend themselves. Their

motives are often selfish, not moral. The weak hope for protection under

the law, and value charity because they hope to be its recipients.

Much of the time their apparent love of morality is just self-interest.

This may well be true. But their selfish motives do not mean that

kindness, charity, and laws, are wrong. It is possible to love genuinely

good things for the wrong reasons.

Nietzsche, the diabolical saint of acceptance tries to accept

everything as a consequence of unconditional love. But when he tries to

accept Nature, he finds a charnel house of death and destruction, the

strong consuming the weak. Out of love and compassion he will send the

weak to the gas chambers and deny their pleas for help because in not

accepting their fate, the weak are rejecting life. They must be shown

the light. Those who seek to protect the weak he regards as the

naysayers.

One senses, at times, Nietzsche’s reluctance to keep following this

line of thought. He is going to overcome his disgust at brutality in a

heroic act of acceptance. It is his idiot compassion that leads him to

embrace ruthless domination and name Napoleon as a

hero.

Like some kind of wannabe savior, Nietzsche takes on the weight of the

world. In his desire to supplant God and Jesus and to get people to

embrace godlessness, Nietzsche strongly resembles Dostoevsky’s character

Kirillov in

The Devils, also known as

The Possessed.

Both become the rivals of God and Christ. They will save us from

salvation, unredeem redemption and promise us eternal death. To do this,

we must embrace our own nothingness and give up dreams of the divine;

except the transcendental vision remains intact because to do this would

be an immense overcoming. Nietzsche and Kirillov are grandiose in their

aspirations and retain strong intimations of religiosity. Zarathustra

is a prophet after all. They are as god-fixated as any theist.

Apparently, Kirillov confused critics because he has many of the same

virtues as Dostoevsky’s Christ-like Prince Myshkin in

The Idiot. But Dostoevsky did this to show that truly demonic behavior can arise from the best of intentions.

Kirillov points out that the major draw card of religions is the

promise of eternal life. No billionaire can offer such a thing. Kirillov

hopes to overcome the fear of death through his suicide. If death is

not to be feared, then religion becomes that much less attractive.

Kirillov is in competition with Christ. Nietzsche is too and in fact is

quite indignant about his inferior status. It seems likely that now, at

least for some people, Nietzsche is indeed to be preferred to Christ.

Nietzsche can be compared to a naïve well-meaning undergraduate moral

relativist. Relativism is taught to school children to teach them to be

tolerant. Students will at times attempt to tolerate some of the

greatest horrors ever perpetrated by mankind in order to be good people.

They too, like Nietzsche, strive to be saints of acceptance and they do

so by holding their noses and attempting to embrace slavery and the

Holocaust. It is, however, evil to tolerate evil. Apparently, some of

the children’s teachers who promulgated this rot actually promote this

kind of thinking.

Nietzsche can at times be an excellent psychologist and aphorist. His

claim that each person’s philosophy is a kind of self-confession is

trenchant. He was right to be horrified by John Stuart Mill and

utilitarianism, and by Kant, to a much lesser degree. However, he shared

their rejection of Christian morality and imagined, like them, that he

could improve upon it – but his beyond-man, his Übermensch, never did

arise and produce new solely self-created values. Nietzsche’s

naturalistic metaphysics precludes the attribution of value or the

discovery of it. God is the source of all values. Without him, there is

nihilism; nothing. The materialist and atheist Karl Marx also tried to

supplant Christianity, but just borrows Christian compassion and

charity, but distorts it by making it compulsory. Goodness only exists,

is only good, if it is free.

Nietzsche finds some appropriate targets of nineteenth century

bourgeoise morality and Christianity to criticize but does not come

close to finding any alternative. At the most, Nietzsche can be seen as a

truth-seeker and someone willing to accept unpleasant realities, but in

the end his philosophy fails amid a mass of contradictions.

[1] Many truths are partial, but some more damagingly so than others.

and

are thus connected with eternity, God, and Freedom that the Person has

supreme intrinsic value. There simply is no way around this fact.

Nietzsche, on the other hand, is famous for the notion that God is dead.

This is usually understood to mean that God is dead as a cultural

phenomenon; that all the smart people have become atheists. René Girard

argues in Dionysus Versus the Crucified, however, that this is a

misunderstanding and that the truth is far more complicated. Nietzsche

rejected Christianity in favor of a return to pagan religion and

Dionysus. Dionysus is a trickster god who stirs up trouble, encourages

his own murder by challenging the social hierarchy, only to magically

reappear unharmed afterwards. This is because Dionysus represents the

scapegoat who is falsely blamed for generating a complete social

breakdown in a way that only a god could achieve, who is then murdered,

bringing the community together in shared hatred, unanimity minus one,

and is then credited with creating widespread peace, again in a god-like

manner.

and

are thus connected with eternity, God, and Freedom that the Person has

supreme intrinsic value. There simply is no way around this fact.

Nietzsche, on the other hand, is famous for the notion that God is dead.

This is usually understood to mean that God is dead as a cultural

phenomenon; that all the smart people have become atheists. René Girard

argues in Dionysus Versus the Crucified, however, that this is a

misunderstanding and that the truth is far more complicated. Nietzsche

rejected Christianity in favor of a return to pagan religion and

Dionysus. Dionysus is a trickster god who stirs up trouble, encourages

his own murder by challenging the social hierarchy, only to magically

reappear unharmed afterwards. This is because Dionysus represents the

scapegoat who is falsely blamed for generating a complete social

breakdown in a way that only a god could achieve, who is then murdered,

bringing the community together in shared hatred, unanimity minus one,

and is then credited with creating widespread peace, again in a god-like

manner.  The Bacchae

by Euripides, “Bacchus” being another name for Dionysus, depicts the

threatening, implacable, and undefeatable nature of the scapegoating

dynamic. Dionysus, a long-haired beautiful and effeminate youth, has a

reputation for stirring up the Bacchae, the female followers of Bacchus,

into a mad murderous frenzy that would likely include wild drinking.

Pentheus, the king of Thebes, wants nothing to do with Dionysus and

tries to eject him from the city but, failing that, ends up imprisoning

him. Dionysus warns Pentheus that he will be sorry for interfering with a

god, an earthquake sets Dionysus free from his prison, and everything

goes to hell for Pentheus who loses his head, literally, at the hands of

his own mother who has become one of the bacchants.

The Bacchae

by Euripides, “Bacchus” being another name for Dionysus, depicts the

threatening, implacable, and undefeatable nature of the scapegoating

dynamic. Dionysus, a long-haired beautiful and effeminate youth, has a

reputation for stirring up the Bacchae, the female followers of Bacchus,

into a mad murderous frenzy that would likely include wild drinking.

Pentheus, the king of Thebes, wants nothing to do with Dionysus and

tries to eject him from the city but, failing that, ends up imprisoning

him. Dionysus warns Pentheus that he will be sorry for interfering with a

god, an earthquake sets Dionysus free from his prison, and everything

goes to hell for Pentheus who loses his head, literally, at the hands of

his own mother who has become one of the bacchants. resentment,

that unlovely emotion and attitude, but it is better than the strong’s

treatment of the weak. Repressed violence is better than violence

expressed.

resentment,

that unlovely emotion and attitude, but it is better than the strong’s

treatment of the weak. Repressed violence is better than violence

expressed. Thus Spake Zarathustra

is where Nietzsche announces the death of God and has the prophet claim

that we have murdered him with our bloody knives. Girard points out

that this is simply not taken seriously by many critics who imagine that

he is referring to the Christian God and that the reference to knives

is strictly metaphorical. But it is Dionysus the god, the scapegoat

victim, that we kill with our knives whereupon he is resurrected as

immortal savior, to begin the process all over again.

Thus Spake Zarathustra

is where Nietzsche announces the death of God and has the prophet claim

that we have murdered him with our bloody knives. Girard points out

that this is simply not taken seriously by many critics who imagine that

he is referring to the Christian God and that the reference to knives

is strictly metaphorical. But it is Dionysus the god, the scapegoat

victim, that we kill with our knives whereupon he is resurrected as

immortal savior, to begin the process all over again.

It

should be pointed out that Nietzsche definitely did not believe in

actual reincarnation. This idea of eternal recurrence is just a thought

experiment to determine a person’s fundamental attitude to life. The

question is how someone reacts to the mere thought of this situation.

This is where the partial truth enters. It can sometimes seem nice to

fantasize about editing our lives; taking out all the boring bits, and

the suffering and the times we acted badly. But saying yes to life is

accepting it just as it is. However, what the test of eternal recurrence

misses is embracing development; the striving part. Living the same

life over and over would be a kind of hell because a person would never

get to develop. A good life combines development and acceptance. In

abandoning development, it is Nietzsche who is rejecting an important

aspect of life.

It

should be pointed out that Nietzsche definitely did not believe in

actual reincarnation. This idea of eternal recurrence is just a thought

experiment to determine a person’s fundamental attitude to life. The

question is how someone reacts to the mere thought of this situation.

This is where the partial truth enters. It can sometimes seem nice to

fantasize about editing our lives; taking out all the boring bits, and

the suffering and the times we acted badly. But saying yes to life is

accepting it just as it is. However, what the test of eternal recurrence

misses is embracing development; the striving part. Living the same

life over and over would be a kind of hell because a person would never

get to develop. A good life combines development and acceptance. In

abandoning development, it is Nietzsche who is rejecting an important

aspect of life. cannot

read, or write; they may not even be toilet trained, but they may

still be a perfect little two year old. We are all at some level of

development and are perfect in this way too. But loving that two year

old also means not condemning them to the same mistakes, the same

interests, the same level of cognitive development for all eternity. In

some sense, we are all that two year old. By trying to say yes to life,

Nietzsche says no to life.

cannot

read, or write; they may not even be toilet trained, but they may

still be a perfect little two year old. We are all at some level of

development and are perfect in this way too. But loving that two year

old also means not condemning them to the same mistakes, the same

interests, the same level of cognitive development for all eternity. In

some sense, we are all that two year old. By trying to say yes to life,

Nietzsche says no to life.

hero.

Like some kind of wannabe savior, Nietzsche takes on the weight of the

world. In his desire to supplant God and Jesus and to get people to

embrace godlessness, Nietzsche strongly resembles Dostoevsky’s character

Kirillov in The Devils, also known as The Possessed.

Both become the rivals of God and Christ. They will save us from

salvation, unredeem redemption and promise us eternal death. To do this,

we must embrace our own nothingness and give up dreams of the divine;

except the transcendental vision remains intact because to do this would

be an immense overcoming. Nietzsche and Kirillov are grandiose in their

aspirations and retain strong intimations of religiosity. Zarathustra

is a prophet after all. They are as god-fixated as any theist.

Apparently, Kirillov confused critics because he has many of the same

virtues as Dostoevsky’s Christ-like Prince Myshkin in The Idiot. But Dostoevsky did this to show that truly demonic behavior can arise from the best of intentions.

hero.

Like some kind of wannabe savior, Nietzsche takes on the weight of the

world. In his desire to supplant God and Jesus and to get people to

embrace godlessness, Nietzsche strongly resembles Dostoevsky’s character

Kirillov in The Devils, also known as The Possessed.

Both become the rivals of God and Christ. They will save us from

salvation, unredeem redemption and promise us eternal death. To do this,

we must embrace our own nothingness and give up dreams of the divine;

except the transcendental vision remains intact because to do this would

be an immense overcoming. Nietzsche and Kirillov are grandiose in their

aspirations and retain strong intimations of religiosity. Zarathustra

is a prophet after all. They are as god-fixated as any theist.

Apparently, Kirillov confused critics because he has many of the same

virtues as Dostoevsky’s Christ-like Prince Myshkin in The Idiot. But Dostoevsky did this to show that truly demonic behavior can arise from the best of intentions.